The Kaziranga

Pre-Trip Extension 2015

February 22-27, 2015

Price: $3,595

Single Supplement: $810

Join us on Facebook at: Follow Hoot Hollow

Rhinoceroses are among the most endangered large mammal on earth. At one time, the Indian One-horned Rhino was seriously endangered, and although still threatened, protection has brought this species back from the brink. At least for now. Of all the rhinos, the One-horned is the most prehistoric looking, with blocky shoulder and hip plates, studded in places with what looks like rivets. It can be seen in only a few locales, and I've been to the two best, and we're going to the very best location to see this prehistoric creature, Kaziranga National Park in northeastern India.

Rhinoceroses are among the most endangered large mammal on earth. At one time, the Indian One-horned Rhino was seriously endangered, and although still threatened, protection has brought this species back from the brink. At least for now. Of all the rhinos, the One-horned is the most prehistoric looking, with blocky shoulder and hip plates, studded in places with what looks like rivets. It can be seen in only a few locales, and I've been to the two best, and we're going to the very best location to see this prehistoric creature, Kaziranga National Park in northeastern India.

Here is a sobering statistic:

There are five species of rhinoceros in the world, and all are threatened with extinction. In parts of Africa, rhinos (both the Black and the White) are being slaughtered for their horns around every 18 hours. A rhino's gestation period is 15 months for a black, 16 for a white, so in the period of a single pregnancy for a white rhino six hundred and eight rhinos will be killed based upon the present rate. It is estimated that there are around 4,000 black rhinos still wild in Africa, so if the poaching was targeted solely to that species, Black Rhinos have less than nine years left before extinction. Fortunately, if one can use that word in this case, white rhinos are also targeted, and there are 14,000 or so remaining of that species, but again, at the present rate, both species would be extinct within forty years!

While the focus of our trip is certainly photographing the rhinos, that task will be relatively easy, and we should have good opportunities on virtually every game drive we do in their territory. But Kaziranga has much more to offer.....

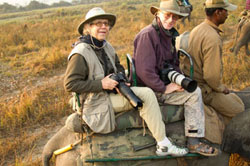

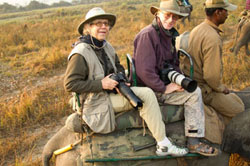

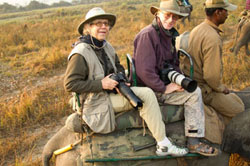

We'll be doing our wildlife viewing two ways. One of the most fun is from the back of elephants, where we'll travel into the high elephant grass and through swamps and marshes looking for rhinos, which are amazingly tolerant of the elephants and allows extremely close approaches. A 70-200 or similar lens is all you need here! From elephant back, we may be shooting several other mammal species, including any of the terrestrial species described below. For a great idea of this trip, I've included the Scouting Report of our 2013 Kaziranga trip to see what we photographed and to give you a great idea of the entire experience. You'll find that at the end of this brochure.

Although viewer sightings wouldn't show it, Kaziranga has the greatest density of tigers than anywhere else in India! The typical tourist doesn't see a tiger, and probably not even a tiger track, but they are there, obscured from view by the six foot tall elephant grass. However, on the rare occasions that tigers are visible, they can present an incredible show, as they are as habituated to vehicles as they are in any of the tiger parks. If we're lucky, we might have a tiger walking down a game track, or stalking the shoreline of the numerous waterways that make up the park. But we're not thinking about tigers here.

Instead, Kaziranga offers one of the best opportunities for photographing wild Indian Elephants. In some locales, Indian elephants can be quite aggressive, and vehicles must maintain a safe distance to avoid being charged. But in Kaziranga the elephants are not aggressive and getting good photos are likely.

Wild Asiatic Buffalo, or water buffalo, are common here, and the wild species often sport huge, sweeping horns. We often find them soaking in ponds or streams, sometimes quite close to the road.

Rhesus Macaques, Assamese Macaques, Capped Langurs, Hoolock Gibbons, Indian Fruit Bats, Indian smooth-coated otters, jungle cats, Wild Boar, Hog, Barasinga, and spotted deer are other mammals we may see and photograph, in addition to a variety of birds, including the spectacular Giant Hornbill, a huge billed bird we might photograph roosting or flying across our game tracks.

One afternoon we'll do a boat cruise where we'll see and attempt to photograph the Ganges River Dolphin, another endangered species. Living in muddy water these dolphins are virtually blind, but like all dolphins they like to breach and it is a challenge to photograph one as it rises out of the water.

We'll have four full days in Kaziranga, game-driving or doing elephant-back safaris at dawn, and game-driving most afternoons. One afternoon we'll go to the Brahmaputra River for a change of pace, hopefully to capture a Ganges River Dolphin.

Our base is one of the most beautiful and luxurious lodges we've stayed in, anywhere, with incredible food and a very accommodating staff. When we did our scouting trip, everyone loved Kaziranga, and many felt that it was their favorite shooting location for the entire trip!

Contact our Office if you are interested,

and please continue and read the trip report that

is posted directly below.

See our Tigers and the Wildlife of India Trip Report

Read our Snow Leopard Expedition Trip Report

If you'd like the latest information on our trips, sign up for our email newsletter. We DO NOT share our email list with anyone.

Join us on Facebook at: Follow Hoot Hollow

.

Our 2013 Scouting Trip Report

Feb. 24, 2013

To Kaziranga

We had a reasonable flight time for our trip to Kaziranga, with a departure at 10:50. Indian airport security is thorough, and after having our carry-on bags X-rayed and the luggage tag stamped, we had two more checkpoints before entering the plane. It was a fairly large jet, fully booked, but with plenty of overhead space and thus the flight went smoothly.

We were met at the Guwathati Airport where, upon disembarking, our ticket was checked, either for security or to insure we didn’t get off at the wrong stop. Once, going to Komodo Island from Bali, we disembarked at the wrong stop on the island of Flores, and luckily discovered our error before our plane took off. I appreciated this extra check here.

The drive west to Kaziranga went uneventfully, with much of the route on a highway where cows, oncoming traffic, or pedestrians were not a problem. The highway, winding along some roads but basically following the floodplain of the Brahmaputra River was relatively level, passing floodplains, dried rice fields, and small villages once we left the main town. Guwathati has a population of 2.5 million, but the drive through town was relatively hornless, no beeping, and much less chaotic than Delhi or Agra. We passed a fancy bannered building, the grand opening of a new Gold’s Gymn.

The drive west to Kaziranga went uneventfully, with much of the route on a highway where cows, oncoming traffic, or pedestrians were not a problem. The highway, winding along some roads but basically following the floodplain of the Brahmaputra River was relatively level, passing floodplains, dried rice fields, and small villages once we left the main town. Guwathati has a population of 2.5 million, but the drive through town was relatively hornless, no beeping, and much less chaotic than Delhi or Agra. We passed a fancy bannered building, the grand opening of a new Gold’s Gymn.

The drive west, with two stops, took about five hours and near our lodge we stopped at an overlook where Hog Deer, Barking Deer, and five One-Horned Rhinos grazed in the wetlands. Several armed guards were standing at the overlook, and we assumed they were guards, but while we still watched the rhinos the guards disappeared. Other locals appeared, and many kids, and I suspect the rhino watching is a local attraction.

We reached our lodge at dusk and were greeted by a competent, English-speaking staff and shown to our rooms, elevated on pillars and extremely comfortable and spacious. All told, the indicators are that we will enjoy this leg of the journey.

Feb. 25. Kaziranga

We left at 6 for a 6:30 elephant ride into the grasses for One-horned Rhinos. We were the second shift, but the sun was just 45 minutes above the horizon and the light still golden and low. I can’t imagine starting earlier and dealing with almost dusk conditions. Mounting the elephants was extremely efficient – we climbed a cement stairway to a large pavilion and stepped aboard our elephant, two to an elephant. Mary’s elephant took three, so she rode with Richard and Delphine.

We were warned, or potentially scared off, that the elephant ride was extremely uncomfortable as the seat required you to literally straddle the elephant as you might a horse, and that the rocking gait was very taxing on the back. We did not find this to be so, although all of us did walk a bit like bow-legged cowpokes after a long trail ride when we did get off the elephants.

One-horned rhinos were everywhere and we hadn’t progressed too far through the patchwork of burnt thatches of elephant grass and green growth when we encountered a mating pair that, with high pitched squeals, ran through the tall grasses and into an opening, kicking up golden puffs of dust against the early light. Soon after, we moved close to a mother rhino and calf and another adult, who ignored our presence atop the elephants.

One-horned rhinos were everywhere and we hadn’t progressed too far through the patchwork of burnt thatches of elephant grass and green growth when we encountered a mating pair that, with high pitched squeals, ran through the tall grasses and into an opening, kicking up golden puffs of dust against the early light. Soon after, we moved close to a mother rhino and calf and another adult, who ignored our presence atop the elephants.

The challenge here was getting a clear shot of a rhino lifting its head, as most were busy munching into the grasses. Hog Deer, the nearest relative to the Spotted Deer that is so common throughout most of India, but absent here, were approachable as well, and we had a pair of males with their stout, distinctive three tined horns. So, too, were the barasingha Deer, the Swamp Deer, which ignored our presence. A variant of this elk-sized deer is found in Kanha, and is called the ‘hard ground’ barasingha, as the habitat there is not the typical swampy environs as present in Kaziranga.

After our ride and a picnic breakfast we did a game drive, two to a vehicle, into the park, photographing more rhinos, hog deer, and numerous birds. In total we probably added another 20 species to our list, without really trying at all. Perhaps the best was a clear view of a Giant Hornbill, a turkey-sized, basically black and  yellow-white bird with a huge bill topped by a long crest. While we watched the bird hopped higher and higher into the branches, finally settling on a bare, thin limb at the very top. There it called a few times, a resonating, honking ring, and I wondered if the extra tube of beak above the bird’s upper mandible played any role in this resonance. Some dinosaurs, and birds are now considered the living fossil cousins of these extinct reptiles, also had odd skull ornaments, sweeping bone structures that extended far beyond their head or cresting high above their nose – much like the Cassowary bird of Australia and New Guinea. Sitting at the edge of the Bharaputra flood plain, it was easy to imagine a Jurassic swamp where the air reverberated from the distant honking of some dinosaur. Our hornbill finally took off, signaling its

yellow-white bird with a huge bill topped by a long crest. While we watched the bird hopped higher and higher into the branches, finally settling on a bare, thin limb at the very top. There it called a few times, a resonating, honking ring, and I wondered if the extra tube of beak above the bird’s upper mandible played any role in this resonance. Some dinosaurs, and birds are now considered the living fossil cousins of these extinct reptiles, also had odd skull ornaments, sweeping bone structures that extended far beyond their head or cresting high above their nose – much like the Cassowary bird of Australia and New Guinea. Sitting at the edge of the Bharaputra flood plain, it was easy to imagine a Jurassic swamp where the air reverberated from the distant honking of some dinosaur. Our hornbill finally took off, signaling its  intention by dropping a load of excrement, and flew towards us. I’d mounted my 500 on my tripod beforehand, luckily, making for a fairly smooth pan as the bird flew to and over us. By noon the light was high and the air hot, and we returned back to camp for a quick lunch and a 2:15 return to the park.

intention by dropping a load of excrement, and flew towards us. I’d mounted my 500 on my tripod beforehand, luckily, making for a fairly smooth pan as the bird flew to and over us. By noon the light was high and the air hot, and we returned back to camp for a quick lunch and a 2:15 return to the park.

PM. We entered the western gate this afternoon, in contrast to the bit more crowded Central Gate where we boarded our elephants this morning. The rhino shooting from the jeeps was outstanding, and we had several opportunities for close-ups as rhinos fed in the open and close to the road. A small herd of wild Indian Elephants visited the lake shore, giving us some OK family shots at some distance in the soft afternoon light. We had a good view of an Asian Barred Owlet and, close by, a poor view of a Brown Fish Owl.

At a viewing platform overlooking Duva Lake a large group of perhaps twenty Smooth-coated Otters (Lutrogale perspicillata) swam about, catching three large fish within a minute of each other. Some charged in to attempt to share but the successful ones seemed to always keep their prize. Occasionally the otters would start calling, sounding remarkably like the Giant Otters of the Pantanal. Unfortunately they never swam close for anything other than tiny white-chinned heads sticking above the river’s surface.

We game-drove until shortly after 6 with the sun dipping a dull red behind the distant western mountains. A bull Asiatic water buffalo floated in the now dingy orange-colored water, its broad, sweeping horns and the boss of its head just visible above the surface. In the starkness of the light the sharp black silhouette of the buffalo accented the shape of the horns, flat, scythe-shaped, and so unlike either its relative the African buffalo or the tiny curly-shaped horns of its domestic relative. As we headed back to camp one Indian Elephant was moving up the highway towards us, carrying a load of banana leaves that extended far out on either side, carrying its dinner home.

Feb. 26. Kaziranga.

Rhesus Macaque Monkeys drinking the nectar from flowers; the lower canine of a One-Horned Rhino is visible -- these teeth are used in fights with other rhinos;

a wild Asiatic Water Buffalo wallowing in the mud.

We had planned on visiting a Gibbon sanctuary far to the east of Kaziranga, but our guide suggested we check out the western part of the park instead where Hoolock Gibbons, Capped Langurs, and Assamese Macaques could be found. The Gibbons viewing here, as described by a friend, was not sexy, as most are seen from the road. Those at the sanctuary require hikes through the forest, the proper atmosphere, but the trip would require about 3 hours each way and, for the photo return, did not seem worth the trouble.

We missed seeing the gibbons, although we heard, quite indistinctly, their almost dog-like hooting far in the distance, in the blue-gray mountains paralleling the highway. Although there are perhaps 2200 one-horned rhinos in Kaziranga, last year several were poached in this area. We heard 60 from a tourist, and 16 from our guide. Either way, it is a terrible waste of life as the horn plays no purpose for anyone but the rhino, and, compared to the African black or white species, it is so insignificant. Last evening we saw a male with a big horn, and I doubt if it was longer than 12 inches in total. Many seemed half that.

Poachers, our guide said, are now using tranquilizers to kill the rhino. With dart guns they subdue the animal, then basically hack off its face as they get every inch of the rhino horn. Our first thought, when we heard tranquilizer, was a ray of hope, as we naively thought that the poachers were simply harvesting the horn, as is done at some game ranches in South Africa. Instead, we learned that the drug dose is nearly fatal as is, but using a dart gun instead of a rifle eliminates the latter’s sharp report. With a dart gun, a poacher can operate almost silently.

Our game drive through this area was rather uneventful, except for a distant view of a Wreathed Hornbill, a near look-alike of the Great but distinguished by an all-white tail. Great hornhills, in contrast, have a black band just above a final terminal band of white, making identification fairly easy.

We drove to the edge of the floodplain where, at this time of year, little water flows and instead the landscape resembles either a desert or a beach, for sand banks extend to the horizon. At an observation tower here, where two people conked their heads soundly on a low overhang as they climbed the steps, we watched a small troop of Assamese Macaques. Quite similar looking to the Rhesus, found through most of India, the Assamese lacks the bright, almost revolting, red rump. Instead, their colors are more sedate, with a grayish head and forequarters  blending to a brown coat that extends down across their rump.

blending to a brown coat that extends down across their rump.

We’d seen a small troop of Capped Langurs when we entered this section, but these huge, black-faced monkeys were shy and bounded off through the trees, presenting no opportunity for shooting. Mary’s driver spotted a family group toward the end of our game drive, saving the morning as we were able to get out of the jeeps, set up tripods, and shoot some clear, but somewhat distant shots, of the family group in the trees high overhead.

On the way back to camp we stopped along the highway for a view of a group of twenty or so Indian Fruit Bats, hanging head-down in a leafless tree above a small house. The bats reminded me of a bag of coins, or a stretched out pair, thin at the top and bulbous, fat at the bottom. I didn’t bring a Range IR with me on this leg of the trip and, once I arrived, I worried that I might have a chance at shooting these big, fruit-eating bats and not have the gear. That hasn’t happened.

PM. We headed back to the western entrance where we had great success yesterday. I didn’t anticipate we could do much better, but we did, by far. Like yesterday, we saw another brown fish owl and the smooth-coated otters swimming far out in the lake but returning along that route we had a One-horned Rhino close to the road and facing us, providing frame-filling verticals whenever, after a half minute or so of grazing, it would raise its head to look our way.

PM. We headed back to the western entrance where we had great success yesterday. I didn’t anticipate we could do much better, but we did, by far. Like yesterday, we saw another brown fish owl and the smooth-coated otters swimming far out in the lake but returning along that route we had a One-horned Rhino close to the road and facing us, providing frame-filling verticals whenever, after a half minute or so of grazing, it would raise its head to look our way.

These rhinos have a unique mouth, quite unlike that of the African species. In Africa, the two species, Black and White, are distinguished most readily by their lips. The black rhino’s upper lip is triangularly shaped, and is prehensile, allowing it to encircle leaves that it then strips off a branch by a tug of its head. White rhinos have a square-lipped appearance, and very much like cows are grazers. The Indian one-horned rhino looks like a cross of the two, as the upper lip is triangular and the lower, which juts forward under a very prominent, heavy lower jaw, is thick-lipped and nearly square.

This lower jaw, which when slightly agape may reveal a sharp-looking, triangular canine tooth or tusk, may, along with the weird plate-like folds of skin that resembles medieval armor, complete with round stud-like protrusions that could be mistaken for rivets anchoring these plates, gives this rhino the most prehistoric appearance of any mammal. Looking at one, its easy to think of a triceratops from the Cretaceous Period. Our rhino tonight was close enough that the pink areas around its irises were visible, tiny eyes in a huge, blocky head.

Our rhino moved closer and we backed off, assuming it wished to cross the road. It eventually did so, but not in the gap we provided but instead right behind Tom and Mary’s jeep. We continued on, and in one of the mud wallows close to the road we found a large bull Asiatic Buffalo wallowing, its skin completely covered in a slick, black mud. The buffalo left the water twice but returned each time for another bout of wallowing, then moved off, digging up the ground or tossing up vegetation with its huge curved horns.

My driver thought he had a tiger when he saw hog deer running off, and we spent about twenty minutes scanning the grasses but nothing appeared, and no alarm calls indicated that a tiger was present. We moved on, shooting the last good light of the day with another buffalo, completely submerged except for the ridge of its back and its head, just below ear level. A Common Kingfisher perched nearby and periodically smashed into the water nearby, and I tried to get a shot where the bird was in focus and the buffalo behind, but the plane was too shallow and I missed. A flock of Jungle Mynahs flew in, circled the buffalo, and perched there momentarily, either to drink or hunt bugs, and as they flew off we returned to the supposed tiger location where we waited, fruitlessly, until the last light of the day.

My driver thought he had a tiger when he saw hog deer running off, and we spent about twenty minutes scanning the grasses but nothing appeared, and no alarm calls indicated that a tiger was present. We moved on, shooting the last good light of the day with another buffalo, completely submerged except for the ridge of its back and its head, just below ear level. A Common Kingfisher perched nearby and periodically smashed into the water nearby, and I tried to get a shot where the bird was in focus and the buffalo behind, but the plane was too shallow and I missed. A flock of Jungle Mynahs flew in, circled the buffalo, and perched there momentarily, either to drink or hunt bugs, and as they flew off we returned to the supposed tiger location where we waited, fruitlessly, until the last light of the day.

A wild Water Buffalo with Jungle Mynas;

a Langur leaping;

barasingha Deer at dawn.

Feb. 27.

We left at 6 for another elephant ride into rhino country. This time, most of us were prepared for the long, cold drive along the main road to the central gate, and Mary and I had on wool caps, a windbreaker, vest, and polarfleece sweater. Our seven were divided amongst three elephants this time, with Tom riding with a ranger on a small elephant and the rest of us split between two adults, three to a chair.

The rhino viewing was as good as our first day, although this time we also had a mother with a young calf out in the open. Another, a male with a raw-looking red rump, as if horned when trying to run off, was completely in the open at what may have been a lick. We circled that one for several different angles.

Mary’s elephant came upon a mother Wild Hog with at least four young babies, their coat a well-camouflaged blend of stripes and scattered spots upon a tawny background. The mother had held her ground, which was puzzling, until they saw the babies and the thatch-like hut where the hogs lived. The hut, a domed structure of bent grasses about four feet in diameter, had a small entrance hole, now used by the babies but presumably larger, earlier, for passage by the adult. I’ve read of some dwarf swamp hogs that construct ‘houses,’ but was unaware that the bristly, common wild hog does so as well.

Mary’s elephant came upon a mother Wild Hog with at least four young babies, their coat a well-camouflaged blend of stripes and scattered spots upon a tawny background. The mother had held her ground, which was puzzling, until they saw the babies and the thatch-like hut where the hogs lived. The hut, a domed structure of bent grasses about four feet in diameter, had a small entrance hole, now used by the babies but presumably larger, earlier, for passage by the adult. I’ve read of some dwarf swamp hogs that construct ‘houses,’ but was unaware that the bristly, common wild hog does so as well.

Mary also had a very young Hog Deer with vivid spots, the typical fawn pattern common even in North American deer. Tom’s elephant took him to a fresh Tiger kill, an elephant that was killed last night and that was mostly consumed. We’d seen about two dozen vultures, either flying away or perched in nearby trees, and we suspected a kill, which Tom confirmed. Unfortunately the cat had left.

We did quite well with a family of Asiatic Water Buffalo as well, with two babies, one so light colored it almost appeared white and still dangling an umbilical cord. Four females and one lone male comprised the herd, and although similar the horns of the male were a bit broader and longer. Any one of them, however, would have been formidable.

After our elephant ride and breakfast we headed out on our jeep drive, paralleling a river where five days ago a tiger had been seen. I asked how shy the cats are here and was told they are not, and this one, just across the river and within easy reach of a long lens, stayed in view for around twenty minutes.

There was a small controlled fire in the forest where we made our turn-around, and as we drove back towards the entrance we passed another, a huge conflagration of burning elephant grass sometimes casting flames fifteen feet into the air. These burns will promote new growth once the rains arrive, and the fires pass quickly, although I suspect a lot of amphibians and reptiles die each year, not able to escape the flames in time.

At our elephant loading dock, in contrast, we saw a marker where various flood levels had reached. In 2004 the monsoon flood reached almost to the seats on an elephant’s back, and in 1988 the flood extended as high as a person’s head sitting on a seat – a good 12 feet. Animals at that time must leave the park, obviously, and move into the hills. Here, I’m told, poaching is more likely, and the danger of road kills as animals move across the highway paralleling this flood plain must be great.

PM. For a change of pace we headed west and to the Brahmaputra River where, at 2:30PM, we boarded a long, covered boat powered by a put-put diesel engine and cruised upriver for Ganges River Dophins. The river here is flat, calm, and broad, probably about four hundred yards wide. We’d barely left our anchor when the first dolphins arched out of the water, just showing their pinkish backs before disappearing. Traveling up river a few miles we turned and drifted until the dolphins appeared. Here we spent the next hour or so attempting to catch one of these challenging mammals as it broke the water’s surface.

The dolphins, about a dozen in total perhaps, were everywhere, or nowhere, as they would appear in one stretch of river, then another. Eventually we patterned their swimming to two likely areas, but even then the shooting was incredibly difficult as the dolphins would rise and almost porpoise out of the water and down again so quickly that, if your lens wasn’t pointed in the right direction, there was little hope of catching a shot. We were forced to stand or sit at attention, one eye to the viewfinder and the other at the rest of the river, although the latter was pointless as any dolphin that appeared there was gone before we could react. Rarely, a mother and young, or perhaps two dolphins would surface within seconds of each other, but most times, expecting this after missing a rise, was useless.

The dolphins, about a dozen in total perhaps, were everywhere, or nowhere, as they would appear in one stretch of river, then another. Eventually we patterned their swimming to two likely areas, but even then the shooting was incredibly difficult as the dolphins would rise and almost porpoise out of the water and down again so quickly that, if your lens wasn’t pointed in the right direction, there was little hope of catching a shot. We were forced to stand or sit at attention, one eye to the viewfinder and the other at the rest of the river, although the latter was pointless as any dolphin that appeared there was gone before we could react. Rarely, a mother and young, or perhaps two dolphins would surface within seconds of each other, but most times, expecting this after missing a rise, was useless.

Still, it was a fun and challenging exercise and simply seeing this aquatic mammal was a treat. The dolphin is perhaps the closest living look-alike to the marine dinosaur, the Ichthyosaur, and like that dinosaur this dolphin has a long, narrow beak – quite unlike almost any other species. This beak is lined with teeth and, in the mammal field guide, is compared to a Gavial, or Gharial, a crocodilian that also has a long, thin snout for catching fish. Gavial’s thin snouts are perfect for slashing sideways in the water to catch fish, and indeed this dolphin does likewise, having a flexible neck that permits this, unlike most cetacean species. The dolphin lacks a true lens and is blind, finding its prey via echolocating pulses, and it is said to be quite vocal, although we heard nothing.

Still, it was a fun and challenging exercise and simply seeing this aquatic mammal was a treat. The dolphin is perhaps the closest living look-alike to the marine dinosaur, the Ichthyosaur, and like that dinosaur this dolphin has a long, narrow beak – quite unlike almost any other species. This beak is lined with teeth and, in the mammal field guide, is compared to a Gavial, or Gharial, a crocodilian that also has a long, thin snout for catching fish. Gavial’s thin snouts are perfect for slashing sideways in the water to catch fish, and indeed this dolphin does likewise, having a flexible neck that permits this, unlike most cetacean species. The dolphin lacks a true lens and is blind, finding its prey via echolocating pulses, and it is said to be quite vocal, although we heard nothing.

As the sky started to turn golden the dolphin activity slowed, and we headed back to our anchorage and the road home, hoping to encounter the gibbons we’re still missing on the trip. We missed them, although a large troop of Capped Langurs were in the trees above the main highway but the light, by then, had failed and the langurs soon disappeared into the thickness of the forest.

Feb. 28

We left early for our long drive and our flight to Delhi where, tomorrow, we start the next leg of our journey, the Tiger Safari!

Visit our Trip and Scouting Report Pages for more images and an even better idea of what all our trips are like. There you'll find our archived reports from previous years.

The Kaziranga

Pre-Trip Extension 2015

February 22-27, 2015

Price: $3,595

Single Supplement: $810

Join us on Facebook at: Follow Hoot Hollow

Rhinoceroses are among the most endangered large mammal on earth. At one time, the Indian One-horned Rhino was seriously endangered, and although still threatened, protection has brought this species back from the brink. At least for now. Of all the rhinos, the One-horned is the most prehistoric looking, with blocky shoulder and hip plates, studded in places with what looks like rivets. It can be seen in only a few locales, and I've been to the two best, and we're going to the very best location to see this prehistoric creature, Kaziranga National Park in northeastern India.

Rhinoceroses are among the most endangered large mammal on earth. At one time, the Indian One-horned Rhino was seriously endangered, and although still threatened, protection has brought this species back from the brink. At least for now. Of all the rhinos, the One-horned is the most prehistoric looking, with blocky shoulder and hip plates, studded in places with what looks like rivets. It can be seen in only a few locales, and I've been to the two best, and we're going to the very best location to see this prehistoric creature, Kaziranga National Park in northeastern India.

Here is a sobering statistic:

There are five species of rhinoceros in the world, and all are threatened with extinction. In parts of Africa, rhinos (both the Black and the White) are being slaughtered for their horns around every 18 hours. A rhino's gestation period is 15 months for a black, 16 for a white, so in the period of a single pregnancy for a white rhino six hundred and eight rhinos will be killed based upon the present rate. It is estimated that there are around 4,000 black rhinos still wild in Africa, so if the poaching was targeted solely to that species, Black Rhinos have less than nine years left before extinction. Fortunately, if one can use that word in this case, white rhinos are also targeted, and there are 14,000 or so remaining of that species, but again, at the present rate, both species would be extinct within forty years!

While the focus of our trip is certainly photographing the rhinos, that task will be relatively easy, and we should have good opportunities on virtually every game drive we do in their territory. But Kaziranga has much more to offer.....

We'll be doing our wildlife viewing two ways. One of the most fun is from the back of elephants, where we'll travel into the high elephant grass and through swamps and marshes looking for rhinos, which are amazingly tolerant of the elephants and allows extremely close approaches. A 70-200 or similar lens is all you need here! From elephant back, we may be shooting several other mammal species, including any of the terrestrial species described below. For a great idea of this trip, I've included the Scouting Report of our 2013 Kaziranga trip to see what we photographed and to give you a great idea of the entire experience. You'll find that at the end of this brochure.

Although viewer sightings wouldn't show it, Kaziranga has the greatest density of tigers than anywhere else in India! The typical tourist doesn't see a tiger, and probably not even a tiger track, but they are there, obscured from view by the six foot tall elephant grass. However, on the rare occasions that tigers are visible, they can present an incredible show, as they are as habituated to vehicles as they are in any of the tiger parks. If we're lucky, we might have a tiger walking down a game track, or stalking the shoreline of the numerous waterways that make up the park. But we're not thinking about tigers here.

Instead, Kaziranga offers one of the best opportunities for photographing wild Indian Elephants. In some locales, Indian elephants can be quite aggressive, and vehicles must maintain a safe distance to avoid being charged. But in Kaziranga the elephants are not aggressive and getting good photos are likely.

Wild Asiatic Buffalo, or water buffalo, are common here, and the wild species often sport huge, sweeping horns. We often find them soaking in ponds or streams, sometimes quite close to the road.

Rhesus Macaques, Assamese Macaques, Capped Langurs, Hoolock Gibbons, Indian Fruit Bats, Indian smooth-coated otters, jungle cats, Wild Boar, Hog, Barasinga, and spotted deer are other mammals we may see and photograph, in addition to a variety of birds, including the spectacular Giant Hornbill, a huge billed bird we might photograph roosting or flying across our game tracks.

One afternoon we'll do a boat cruise where we'll see and attempt to photograph the Ganges River Dolphin, another endangered species. Living in muddy water these dolphins are virtually blind, but like all dolphins they like to breach and it is a challenge to photograph one as it rises out of the water.

We'll have four full days in Kaziranga, game-driving or doing elephant-back safaris at dawn, and game-driving most afternoons. One afternoon we'll go to the Brahmaputra River for a change of pace, hopefully to capture a Ganges River Dolphin.

Our base is one of the most beautiful and luxurious lodges we've stayed in, anywhere, with incredible food and a very accommodating staff. When we did our scouting trip, everyone loved Kaziranga, and many felt that it was their favorite shooting location for the entire trip!

Contact our Office if you are interested,

and please continue and read the trip report that

is posted directly below.

See our Tigers and the Wildlife of India Trip Report

Read our Snow Leopard Expedition Trip Report

If you'd like the latest information on our trips, sign up for our email newsletter. We DO NOT share our email list with anyone.

Join us on Facebook at: Follow Hoot Hollow

.

Our 2013 Scouting Trip Report

Feb. 24, 2013

To Kaziranga

We had a reasonable flight time for our trip to Kaziranga, with a departure at 10:50. Indian airport security is thorough, and after having our carry-on bags X-rayed and the luggage tag stamped, we had two more checkpoints before entering the plane. It was a fairly large jet, fully booked, but with plenty of overhead space and thus the flight went smoothly.

We were met at the Guwathati Airport where, upon disembarking, our ticket was checked, either for security or to insure we didn’t get off at the wrong stop. Once, going to Komodo Island from Bali, we disembarked at the wrong stop on the island of Flores, and luckily discovered our error before our plane took off. I appreciated this extra check here.

The drive west to Kaziranga went uneventfully, with much of the route on a highway where cows, oncoming traffic, or pedestrians were not a problem. The highway, winding along some roads but basically following the floodplain of the Brahmaputra River was relatively level, passing floodplains, dried rice fields, and small villages once we left the main town. Guwathati has a population of 2.5 million, but the drive through town was relatively hornless, no beeping, and much less chaotic than Delhi or Agra. We passed a fancy bannered building, the grand opening of a new Gold’s Gymn.

The drive west to Kaziranga went uneventfully, with much of the route on a highway where cows, oncoming traffic, or pedestrians were not a problem. The highway, winding along some roads but basically following the floodplain of the Brahmaputra River was relatively level, passing floodplains, dried rice fields, and small villages once we left the main town. Guwathati has a population of 2.5 million, but the drive through town was relatively hornless, no beeping, and much less chaotic than Delhi or Agra. We passed a fancy bannered building, the grand opening of a new Gold’s Gymn.

The drive west, with two stops, took about five hours and near our lodge we stopped at an overlook where Hog Deer, Barking Deer, and five One-Horned Rhinos grazed in the wetlands. Several armed guards were standing at the overlook, and we assumed they were guards, but while we still watched the rhinos the guards disappeared. Other locals appeared, and many kids, and I suspect the rhino watching is a local attraction.

We reached our lodge at dusk and were greeted by a competent, English-speaking staff and shown to our rooms, elevated on pillars and extremely comfortable and spacious. All told, the indicators are that we will enjoy this leg of the journey.

Feb. 25. Kaziranga

We left at 6 for a 6:30 elephant ride into the grasses for One-horned Rhinos. We were the second shift, but the sun was just 45 minutes above the horizon and the light still golden and low. I can’t imagine starting earlier and dealing with almost dusk conditions. Mounting the elephants was extremely efficient – we climbed a cement stairway to a large pavilion and stepped aboard our elephant, two to an elephant. Mary’s elephant took three, so she rode with Richard and Delphine.

We were warned, or potentially scared off, that the elephant ride was extremely uncomfortable as the seat required you to literally straddle the elephant as you might a horse, and that the rocking gait was very taxing on the back. We did not find this to be so, although all of us did walk a bit like bow-legged cowpokes after a long trail ride when we did get off the elephants.

One-horned rhinos were everywhere and we hadn’t progressed too far through the patchwork of burnt thatches of elephant grass and green growth when we encountered a mating pair that, with high pitched squeals, ran through the tall grasses and into an opening, kicking up golden puffs of dust against the early light. Soon after, we moved close to a mother rhino and calf and another adult, who ignored our presence atop the elephants.

One-horned rhinos were everywhere and we hadn’t progressed too far through the patchwork of burnt thatches of elephant grass and green growth when we encountered a mating pair that, with high pitched squeals, ran through the tall grasses and into an opening, kicking up golden puffs of dust against the early light. Soon after, we moved close to a mother rhino and calf and another adult, who ignored our presence atop the elephants.

The challenge here was getting a clear shot of a rhino lifting its head, as most were busy munching into the grasses. Hog Deer, the nearest relative to the Spotted Deer that is so common throughout most of India, but absent here, were approachable as well, and we had a pair of males with their stout, distinctive three tined horns. So, too, were the barasingha Deer, the Swamp Deer, which ignored our presence. A variant of this elk-sized deer is found in Kanha, and is called the ‘hard ground’ barasingha, as the habitat there is not the typical swampy environs as present in Kaziranga.

After our ride and a picnic breakfast we did a game drive, two to a vehicle, into the park, photographing more rhinos, hog deer, and numerous birds. In total we probably added another 20 species to our list, without really trying at all. Perhaps the best was a clear view of a Giant Hornbill, a turkey-sized, basically black and  yellow-white bird with a huge bill topped by a long crest. While we watched the bird hopped higher and higher into the branches, finally settling on a bare, thin limb at the very top. There it called a few times, a resonating, honking ring, and I wondered if the extra tube of beak above the bird’s upper mandible played any role in this resonance. Some dinosaurs, and birds are now considered the living fossil cousins of these extinct reptiles, also had odd skull ornaments, sweeping bone structures that extended far beyond their head or cresting high above their nose – much like the Cassowary bird of Australia and New Guinea. Sitting at the edge of the Bharaputra flood plain, it was easy to imagine a Jurassic swamp where the air reverberated from the distant honking of some dinosaur. Our hornbill finally took off, signaling its

yellow-white bird with a huge bill topped by a long crest. While we watched the bird hopped higher and higher into the branches, finally settling on a bare, thin limb at the very top. There it called a few times, a resonating, honking ring, and I wondered if the extra tube of beak above the bird’s upper mandible played any role in this resonance. Some dinosaurs, and birds are now considered the living fossil cousins of these extinct reptiles, also had odd skull ornaments, sweeping bone structures that extended far beyond their head or cresting high above their nose – much like the Cassowary bird of Australia and New Guinea. Sitting at the edge of the Bharaputra flood plain, it was easy to imagine a Jurassic swamp where the air reverberated from the distant honking of some dinosaur. Our hornbill finally took off, signaling its  intention by dropping a load of excrement, and flew towards us. I’d mounted my 500 on my tripod beforehand, luckily, making for a fairly smooth pan as the bird flew to and over us. By noon the light was high and the air hot, and we returned back to camp for a quick lunch and a 2:15 return to the park.

intention by dropping a load of excrement, and flew towards us. I’d mounted my 500 on my tripod beforehand, luckily, making for a fairly smooth pan as the bird flew to and over us. By noon the light was high and the air hot, and we returned back to camp for a quick lunch and a 2:15 return to the park.

PM. We entered the western gate this afternoon, in contrast to the bit more crowded Central Gate where we boarded our elephants this morning. The rhino shooting from the jeeps was outstanding, and we had several opportunities for close-ups as rhinos fed in the open and close to the road. A small herd of wild Indian Elephants visited the lake shore, giving us some OK family shots at some distance in the soft afternoon light. We had a good view of an Asian Barred Owlet and, close by, a poor view of a Brown Fish Owl.

At a viewing platform overlooking Duva Lake a large group of perhaps twenty Smooth-coated Otters (Lutrogale perspicillata) swam about, catching three large fish within a minute of each other. Some charged in to attempt to share but the successful ones seemed to always keep their prize. Occasionally the otters would start calling, sounding remarkably like the Giant Otters of the Pantanal. Unfortunately they never swam close for anything other than tiny white-chinned heads sticking above the river’s surface.

We game-drove until shortly after 6 with the sun dipping a dull red behind the distant western mountains. A bull Asiatic water buffalo floated in the now dingy orange-colored water, its broad, sweeping horns and the boss of its head just visible above the surface. In the starkness of the light the sharp black silhouette of the buffalo accented the shape of the horns, flat, scythe-shaped, and so unlike either its relative the African buffalo or the tiny curly-shaped horns of its domestic relative. As we headed back to camp one Indian Elephant was moving up the highway towards us, carrying a load of banana leaves that extended far out on either side, carrying its dinner home.

Feb. 26. Kaziranga.

Rhesus Macaque Monkeys drinking the nectar from flowers; the lower canine of a One-Horned Rhino is visible -- these teeth are used in fights with other rhinos;

a wild Asiatic Water Buffalo wallowing in the mud.

We had planned on visiting a Gibbon sanctuary far to the east of Kaziranga, but our guide suggested we check out the western part of the park instead where Hoolock Gibbons, Capped Langurs, and Assamese Macaques could be found. The Gibbons viewing here, as described by a friend, was not sexy, as most are seen from the road. Those at the sanctuary require hikes through the forest, the proper atmosphere, but the trip would require about 3 hours each way and, for the photo return, did not seem worth the trouble.

We missed seeing the gibbons, although we heard, quite indistinctly, their almost dog-like hooting far in the distance, in the blue-gray mountains paralleling the highway. Although there are perhaps 2200 one-horned rhinos in Kaziranga, last year several were poached in this area. We heard 60 from a tourist, and 16 from our guide. Either way, it is a terrible waste of life as the horn plays no purpose for anyone but the rhino, and, compared to the African black or white species, it is so insignificant. Last evening we saw a male with a big horn, and I doubt if it was longer than 12 inches in total. Many seemed half that.

Poachers, our guide said, are now using tranquilizers to kill the rhino. With dart guns they subdue the animal, then basically hack off its face as they get every inch of the rhino horn. Our first thought, when we heard tranquilizer, was a ray of hope, as we naively thought that the poachers were simply harvesting the horn, as is done at some game ranches in South Africa. Instead, we learned that the drug dose is nearly fatal as is, but using a dart gun instead of a rifle eliminates the latter’s sharp report. With a dart gun, a poacher can operate almost silently.

Our game drive through this area was rather uneventful, except for a distant view of a Wreathed Hornbill, a near look-alike of the Great but distinguished by an all-white tail. Great hornhills, in contrast, have a black band just above a final terminal band of white, making identification fairly easy.

We drove to the edge of the floodplain where, at this time of year, little water flows and instead the landscape resembles either a desert or a beach, for sand banks extend to the horizon. At an observation tower here, where two people conked their heads soundly on a low overhang as they climbed the steps, we watched a small troop of Assamese Macaques. Quite similar looking to the Rhesus, found through most of India, the Assamese lacks the bright, almost revolting, red rump. Instead, their colors are more sedate, with a grayish head and forequarters  blending to a brown coat that extends down across their rump.

blending to a brown coat that extends down across their rump.

We’d seen a small troop of Capped Langurs when we entered this section, but these huge, black-faced monkeys were shy and bounded off through the trees, presenting no opportunity for shooting. Mary’s driver spotted a family group toward the end of our game drive, saving the morning as we were able to get out of the jeeps, set up tripods, and shoot some clear, but somewhat distant shots, of the family group in the trees high overhead.

On the way back to camp we stopped along the highway for a view of a group of twenty or so Indian Fruit Bats, hanging head-down in a leafless tree above a small house. The bats reminded me of a bag of coins, or a stretched out pair, thin at the top and bulbous, fat at the bottom. I didn’t bring a Range IR with me on this leg of the trip and, once I arrived, I worried that I might have a chance at shooting these big, fruit-eating bats and not have the gear. That hasn’t happened.

PM. We headed back to the western entrance where we had great success yesterday. I didn’t anticipate we could do much better, but we did, by far. Like yesterday, we saw another brown fish owl and the smooth-coated otters swimming far out in the lake but returning along that route we had a One-horned Rhino close to the road and facing us, providing frame-filling verticals whenever, after a half minute or so of grazing, it would raise its head to look our way.

PM. We headed back to the western entrance where we had great success yesterday. I didn’t anticipate we could do much better, but we did, by far. Like yesterday, we saw another brown fish owl and the smooth-coated otters swimming far out in the lake but returning along that route we had a One-horned Rhino close to the road and facing us, providing frame-filling verticals whenever, after a half minute or so of grazing, it would raise its head to look our way.

These rhinos have a unique mouth, quite unlike that of the African species. In Africa, the two species, Black and White, are distinguished most readily by their lips. The black rhino’s upper lip is triangularly shaped, and is prehensile, allowing it to encircle leaves that it then strips off a branch by a tug of its head. White rhinos have a square-lipped appearance, and very much like cows are grazers. The Indian one-horned rhino looks like a cross of the two, as the upper lip is triangular and the lower, which juts forward under a very prominent, heavy lower jaw, is thick-lipped and nearly square.

This lower jaw, which when slightly agape may reveal a sharp-looking, triangular canine tooth or tusk, may, along with the weird plate-like folds of skin that resembles medieval armor, complete with round stud-like protrusions that could be mistaken for rivets anchoring these plates, gives this rhino the most prehistoric appearance of any mammal. Looking at one, its easy to think of a triceratops from the Cretaceous Period. Our rhino tonight was close enough that the pink areas around its irises were visible, tiny eyes in a huge, blocky head.

Our rhino moved closer and we backed off, assuming it wished to cross the road. It eventually did so, but not in the gap we provided but instead right behind Tom and Mary’s jeep. We continued on, and in one of the mud wallows close to the road we found a large bull Asiatic Buffalo wallowing, its skin completely covered in a slick, black mud. The buffalo left the water twice but returned each time for another bout of wallowing, then moved off, digging up the ground or tossing up vegetation with its huge curved horns.

My driver thought he had a tiger when he saw hog deer running off, and we spent about twenty minutes scanning the grasses but nothing appeared, and no alarm calls indicated that a tiger was present. We moved on, shooting the last good light of the day with another buffalo, completely submerged except for the ridge of its back and its head, just below ear level. A Common Kingfisher perched nearby and periodically smashed into the water nearby, and I tried to get a shot where the bird was in focus and the buffalo behind, but the plane was too shallow and I missed. A flock of Jungle Mynahs flew in, circled the buffalo, and perched there momentarily, either to drink or hunt bugs, and as they flew off we returned to the supposed tiger location where we waited, fruitlessly, until the last light of the day.

My driver thought he had a tiger when he saw hog deer running off, and we spent about twenty minutes scanning the grasses but nothing appeared, and no alarm calls indicated that a tiger was present. We moved on, shooting the last good light of the day with another buffalo, completely submerged except for the ridge of its back and its head, just below ear level. A Common Kingfisher perched nearby and periodically smashed into the water nearby, and I tried to get a shot where the bird was in focus and the buffalo behind, but the plane was too shallow and I missed. A flock of Jungle Mynahs flew in, circled the buffalo, and perched there momentarily, either to drink or hunt bugs, and as they flew off we returned to the supposed tiger location where we waited, fruitlessly, until the last light of the day.

A wild Water Buffalo with Jungle Mynas;

a Langur leaping;

barasingha Deer at dawn.

Feb. 27.

We left at 6 for another elephant ride into rhino country. This time, most of us were prepared for the long, cold drive along the main road to the central gate, and Mary and I had on wool caps, a windbreaker, vest, and polarfleece sweater. Our seven were divided amongst three elephants this time, with Tom riding with a ranger on a small elephant and the rest of us split between two adults, three to a chair.

The rhino viewing was as good as our first day, although this time we also had a mother with a young calf out in the open. Another, a male with a raw-looking red rump, as if horned when trying to run off, was completely in the open at what may have been a lick. We circled that one for several different angles.

Mary’s elephant came upon a mother Wild Hog with at least four young babies, their coat a well-camouflaged blend of stripes and scattered spots upon a tawny background. The mother had held her ground, which was puzzling, until they saw the babies and the thatch-like hut where the hogs lived. The hut, a domed structure of bent grasses about four feet in diameter, had a small entrance hole, now used by the babies but presumably larger, earlier, for passage by the adult. I’ve read of some dwarf swamp hogs that construct ‘houses,’ but was unaware that the bristly, common wild hog does so as well.

Mary’s elephant came upon a mother Wild Hog with at least four young babies, their coat a well-camouflaged blend of stripes and scattered spots upon a tawny background. The mother had held her ground, which was puzzling, until they saw the babies and the thatch-like hut where the hogs lived. The hut, a domed structure of bent grasses about four feet in diameter, had a small entrance hole, now used by the babies but presumably larger, earlier, for passage by the adult. I’ve read of some dwarf swamp hogs that construct ‘houses,’ but was unaware that the bristly, common wild hog does so as well.

Mary also had a very young Hog Deer with vivid spots, the typical fawn pattern common even in North American deer. Tom’s elephant took him to a fresh Tiger kill, an elephant that was killed last night and that was mostly consumed. We’d seen about two dozen vultures, either flying away or perched in nearby trees, and we suspected a kill, which Tom confirmed. Unfortunately the cat had left.

We did quite well with a family of Asiatic Water Buffalo as well, with two babies, one so light colored it almost appeared white and still dangling an umbilical cord. Four females and one lone male comprised the herd, and although similar the horns of the male were a bit broader and longer. Any one of them, however, would have been formidable.

After our elephant ride and breakfast we headed out on our jeep drive, paralleling a river where five days ago a tiger had been seen. I asked how shy the cats are here and was told they are not, and this one, just across the river and within easy reach of a long lens, stayed in view for around twenty minutes.

There was a small controlled fire in the forest where we made our turn-around, and as we drove back towards the entrance we passed another, a huge conflagration of burning elephant grass sometimes casting flames fifteen feet into the air. These burns will promote new growth once the rains arrive, and the fires pass quickly, although I suspect a lot of amphibians and reptiles die each year, not able to escape the flames in time.

At our elephant loading dock, in contrast, we saw a marker where various flood levels had reached. In 2004 the monsoon flood reached almost to the seats on an elephant’s back, and in 1988 the flood extended as high as a person’s head sitting on a seat – a good 12 feet. Animals at that time must leave the park, obviously, and move into the hills. Here, I’m told, poaching is more likely, and the danger of road kills as animals move across the highway paralleling this flood plain must be great.

PM. For a change of pace we headed west and to the Brahmaputra River where, at 2:30PM, we boarded a long, covered boat powered by a put-put diesel engine and cruised upriver for Ganges River Dophins. The river here is flat, calm, and broad, probably about four hundred yards wide. We’d barely left our anchor when the first dolphins arched out of the water, just showing their pinkish backs before disappearing. Traveling up river a few miles we turned and drifted until the dolphins appeared. Here we spent the next hour or so attempting to catch one of these challenging mammals as it broke the water’s surface.

The dolphins, about a dozen in total perhaps, were everywhere, or nowhere, as they would appear in one stretch of river, then another. Eventually we patterned their swimming to two likely areas, but even then the shooting was incredibly difficult as the dolphins would rise and almost porpoise out of the water and down again so quickly that, if your lens wasn’t pointed in the right direction, there was little hope of catching a shot. We were forced to stand or sit at attention, one eye to the viewfinder and the other at the rest of the river, although the latter was pointless as any dolphin that appeared there was gone before we could react. Rarely, a mother and young, or perhaps two dolphins would surface within seconds of each other, but most times, expecting this after missing a rise, was useless.

The dolphins, about a dozen in total perhaps, were everywhere, or nowhere, as they would appear in one stretch of river, then another. Eventually we patterned their swimming to two likely areas, but even then the shooting was incredibly difficult as the dolphins would rise and almost porpoise out of the water and down again so quickly that, if your lens wasn’t pointed in the right direction, there was little hope of catching a shot. We were forced to stand or sit at attention, one eye to the viewfinder and the other at the rest of the river, although the latter was pointless as any dolphin that appeared there was gone before we could react. Rarely, a mother and young, or perhaps two dolphins would surface within seconds of each other, but most times, expecting this after missing a rise, was useless.

Still, it was a fun and challenging exercise and simply seeing this aquatic mammal was a treat. The dolphin is perhaps the closest living look-alike to the marine dinosaur, the Ichthyosaur, and like that dinosaur this dolphin has a long, narrow beak – quite unlike almost any other species. This beak is lined with teeth and, in the mammal field guide, is compared to a Gavial, or Gharial, a crocodilian that also has a long, thin snout for catching fish. Gavial’s thin snouts are perfect for slashing sideways in the water to catch fish, and indeed this dolphin does likewise, having a flexible neck that permits this, unlike most cetacean species. The dolphin lacks a true lens and is blind, finding its prey via echolocating pulses, and it is said to be quite vocal, although we heard nothing.

Still, it was a fun and challenging exercise and simply seeing this aquatic mammal was a treat. The dolphin is perhaps the closest living look-alike to the marine dinosaur, the Ichthyosaur, and like that dinosaur this dolphin has a long, narrow beak – quite unlike almost any other species. This beak is lined with teeth and, in the mammal field guide, is compared to a Gavial, or Gharial, a crocodilian that also has a long, thin snout for catching fish. Gavial’s thin snouts are perfect for slashing sideways in the water to catch fish, and indeed this dolphin does likewise, having a flexible neck that permits this, unlike most cetacean species. The dolphin lacks a true lens and is blind, finding its prey via echolocating pulses, and it is said to be quite vocal, although we heard nothing.

As the sky started to turn golden the dolphin activity slowed, and we headed back to our anchorage and the road home, hoping to encounter the gibbons we’re still missing on the trip. We missed them, although a large troop of Capped Langurs were in the trees above the main highway but the light, by then, had failed and the langurs soon disappeared into the thickness of the forest.

Feb. 28

We left early for our long drive and our flight to Delhi where, tomorrow, we start the next leg of our journey, the Tiger Safari!

Visit our Trip and Scouting Report Pages for more images and an even better idea of what all our trips are like. There you'll find our archived reports from previous years.

The Kaziranga

Pre-Trip Extension 2015

February 22-27, 2015

Price: $3,595

Single Supplement: $810

Join us on Facebook at: Follow Hoot Hollow

Rhinoceroses are among the most endangered large mammal on earth. At one time, the Indian One-horned Rhino was seriously endangered, and although still threatened, protection has brought this species back from the brink. At least for now. Of all the rhinos, the One-horned is the most prehistoric looking, with blocky shoulder and hip plates, studded in places with what looks like rivets. It can be seen in only a few locales, and I've been to the two best, and we're going to the very best location to see this prehistoric creature, Kaziranga National Park in northeastern India.

Rhinoceroses are among the most endangered large mammal on earth. At one time, the Indian One-horned Rhino was seriously endangered, and although still threatened, protection has brought this species back from the brink. At least for now. Of all the rhinos, the One-horned is the most prehistoric looking, with blocky shoulder and hip plates, studded in places with what looks like rivets. It can be seen in only a few locales, and I've been to the two best, and we're going to the very best location to see this prehistoric creature, Kaziranga National Park in northeastern India.

Here is a sobering statistic:

There are five species of rhinoceros in the world, and all are threatened with extinction. In parts of Africa, rhinos (both the Black and the White) are being slaughtered for their horns around every 18 hours. A rhino's gestation period is 15 months for a black, 16 for a white, so in the period of a single pregnancy for a white rhino six hundred and eight rhinos will be killed based upon the present rate. It is estimated that there are around 4,000 black rhinos still wild in Africa, so if the poaching was targeted solely to that species, Black Rhinos have less than nine years left before extinction. Fortunately, if one can use that word in this case, white rhinos are also targeted, and there are 14,000 or so remaining of that species, but again, at the present rate, both species would be extinct within forty years!

While the focus of our trip is certainly photographing the rhinos, that task will be relatively easy, and we should have good opportunities on virtually every game drive we do in their territory. But Kaziranga has much more to offer.....

We'll be doing our wildlife viewing two ways. One of the most fun is from the back of elephants, where we'll travel into the high elephant grass and through swamps and marshes looking for rhinos, which are amazingly tolerant of the elephants and allows extremely close approaches. A 70-200 or similar lens is all you need here! From elephant back, we may be shooting several other mammal species, including any of the terrestrial species described below. For a great idea of this trip, I've included the Scouting Report of our 2013 Kaziranga trip to see what we photographed and to give you a great idea of the entire experience. You'll find that at the end of this brochure.

Although viewer sightings wouldn't show it, Kaziranga has the greatest density of tigers than anywhere else in India! The typical tourist doesn't see a tiger, and probably not even a tiger track, but they are there, obscured from view by the six foot tall elephant grass. However, on the rare occasions that tigers are visible, they can present an incredible show, as they are as habituated to vehicles as they are in any of the tiger parks. If we're lucky, we might have a tiger walking down a game track, or stalking the shoreline of the numerous waterways that make up the park. But we're not thinking about tigers here.

Instead, Kaziranga offers one of the best opportunities for photographing wild Indian Elephants. In some locales, Indian elephants can be quite aggressive, and vehicles must maintain a safe distance to avoid being charged. But in Kaziranga the elephants are not aggressive and getting good photos are likely.

Wild Asiatic Buffalo, or water buffalo, are common here, and the wild species often sport huge, sweeping horns. We often find them soaking in ponds or streams, sometimes quite close to the road.

Rhesus Macaques, Assamese Macaques, Capped Langurs, Hoolock Gibbons, Indian Fruit Bats, Indian smooth-coated otters, jungle cats, Wild Boar, Hog, Barasinga, and spotted deer are other mammals we may see and photograph, in addition to a variety of birds, including the spectacular Giant Hornbill, a huge billed bird we might photograph roosting or flying across our game tracks.

One afternoon we'll do a boat cruise where we'll see and attempt to photograph the Ganges River Dolphin, another endangered species. Living in muddy water these dolphins are virtually blind, but like all dolphins they like to breach and it is a challenge to photograph one as it rises out of the water.

We'll have four full days in Kaziranga, game-driving or doing elephant-back safaris at dawn, and game-driving most afternoons. One afternoon we'll go to the Brahmaputra River for a change of pace, hopefully to capture a Ganges River Dolphin.

Our base is one of the most beautiful and luxurious lodges we've stayed in, anywhere, with incredible food and a very accommodating staff. When we did our scouting trip, everyone loved Kaziranga, and many felt that it was their favorite shooting location for the entire trip!

Contact our Office if you are interested,

and please continue and read the trip report that

is posted directly below.

See our Tigers and the Wildlife of India Trip Report

Read our Snow Leopard Expedition Trip Report

If you'd like the latest information on our trips, sign up for our email newsletter. We DO NOT share our email list with anyone.

Join us on Facebook at: Follow Hoot Hollow

.

Our 2013 Scouting Trip Report

Feb. 24, 2013

To Kaziranga

We had a reasonable flight time for our trip to Kaziranga, with a departure at 10:50. Indian airport security is thorough, and after having our carry-on bags X-rayed and the luggage tag stamped, we had two more checkpoints before entering the plane. It was a fairly large jet, fully booked, but with plenty of overhead space and thus the flight went smoothly.

We were met at the Guwathati Airport where, upon disembarking, our ticket was checked, either for security or to insure we didn’t get off at the wrong stop. Once, going to Komodo Island from Bali, we disembarked at the wrong stop on the island of Flores, and luckily discovered our error before our plane took off. I appreciated this extra check here.

The drive west to Kaziranga went uneventfully, with much of the route on a highway where cows, oncoming traffic, or pedestrians were not a problem. The highway, winding along some roads but basically following the floodplain of the Brahmaputra River was relatively level, passing floodplains, dried rice fields, and small villages once we left the main town. Guwathati has a population of 2.5 million, but the drive through town was relatively hornless, no beeping, and much less chaotic than Delhi or Agra. We passed a fancy bannered building, the grand opening of a new Gold’s Gymn.

The drive west to Kaziranga went uneventfully, with much of the route on a highway where cows, oncoming traffic, or pedestrians were not a problem. The highway, winding along some roads but basically following the floodplain of the Brahmaputra River was relatively level, passing floodplains, dried rice fields, and small villages once we left the main town. Guwathati has a population of 2.5 million, but the drive through town was relatively hornless, no beeping, and much less chaotic than Delhi or Agra. We passed a fancy bannered building, the grand opening of a new Gold’s Gymn.

The drive west, with two stops, took about five hours and near our lodge we stopped at an overlook where Hog Deer, Barking Deer, and five One-Horned Rhinos grazed in the wetlands. Several armed guards were standing at the overlook, and we assumed they were guards, but while we still watched the rhinos the guards disappeared. Other locals appeared, and many kids, and I suspect the rhino watching is a local attraction.

We reached our lodge at dusk and were greeted by a competent, English-speaking staff and shown to our rooms, elevated on pillars and extremely comfortable and spacious. All told, the indicators are that we will enjoy this leg of the journey.

Feb. 25. Kaziranga

We left at 6 for a 6:30 elephant ride into the grasses for One-horned Rhinos. We were the second shift, but the sun was just 45 minutes above the horizon and the light still golden and low. I can’t imagine starting earlier and dealing with almost dusk conditions. Mounting the elephants was extremely efficient – we climbed a cement stairway to a large pavilion and stepped aboard our elephant, two to an elephant. Mary’s elephant took three, so she rode with Richard and Delphine.

We were warned, or potentially scared off, that the elephant ride was extremely uncomfortable as the seat required you to literally straddle the elephant as you might a horse, and that the rocking gait was very taxing on the back. We did not find this to be so, although all of us did walk a bit like bow-legged cowpokes after a long trail ride when we did get off the elephants.

One-horned rhinos were everywhere and we hadn’t progressed too far through the patchwork of burnt thatches of elephant grass and green growth when we encountered a mating pair that, with high pitched squeals, ran through the tall grasses and into an opening, kicking up golden puffs of dust against the early light. Soon after, we moved close to a mother rhino and calf and another adult, who ignored our presence atop the elephants.

One-horned rhinos were everywhere and we hadn’t progressed too far through the patchwork of burnt thatches of elephant grass and green growth when we encountered a mating pair that, with high pitched squeals, ran through the tall grasses and into an opening, kicking up golden puffs of dust against the early light. Soon after, we moved close to a mother rhino and calf and another adult, who ignored our presence atop the elephants.

The challenge here was getting a clear shot of a rhino lifting its head, as most were busy munching into the grasses. Hog Deer, the nearest relative to the Spotted Deer that is so common throughout most of India, but absent here, were approachable as well, and we had a pair of males with their stout, distinctive three tined horns. So, too, were the barasingha Deer, the Swamp Deer, which ignored our presence. A variant of this elk-sized deer is found in Kanha, and is called the ‘hard ground’ barasingha, as the habitat there is not the typical swampy environs as present in Kaziranga.

After our ride and a picnic breakfast we did a game drive, two to a vehicle, into the park, photographing more rhinos, hog deer, and numerous birds. In total we probably added another 20 species to our list, without really trying at all. Perhaps the best was a clear view of a Giant Hornbill, a turkey-sized, basically black and  yellow-white bird with a huge bill topped by a long crest. While we watched the bird hopped higher and higher into the branches, finally settling on a bare, thin limb at the very top. There it called a few times, a resonating, honking ring, and I wondered if the extra tube of beak above the bird’s upper mandible played any role in this resonance. Some dinosaurs, and birds are now considered the living fossil cousins of these extinct reptiles, also had odd skull ornaments, sweeping bone structures that extended far beyond their head or cresting high above their nose – much like the Cassowary bird of Australia and New Guinea. Sitting at the edge of the Bharaputra flood plain, it was easy to imagine a Jurassic swamp where the air reverberated from the distant honking of some dinosaur. Our hornbill finally took off, signaling its

yellow-white bird with a huge bill topped by a long crest. While we watched the bird hopped higher and higher into the branches, finally settling on a bare, thin limb at the very top. There it called a few times, a resonating, honking ring, and I wondered if the extra tube of beak above the bird’s upper mandible played any role in this resonance. Some dinosaurs, and birds are now considered the living fossil cousins of these extinct reptiles, also had odd skull ornaments, sweeping bone structures that extended far beyond their head or cresting high above their nose – much like the Cassowary bird of Australia and New Guinea. Sitting at the edge of the Bharaputra flood plain, it was easy to imagine a Jurassic swamp where the air reverberated from the distant honking of some dinosaur. Our hornbill finally took off, signaling its  intention by dropping a load of excrement, and flew towards us. I’d mounted my 500 on my tripod beforehand, luckily, making for a fairly smooth pan as the bird flew to and over us. By noon the light was high and the air hot, and we returned back to camp for a quick lunch and a 2:15 return to the park.

intention by dropping a load of excrement, and flew towards us. I’d mounted my 500 on my tripod beforehand, luckily, making for a fairly smooth pan as the bird flew to and over us. By noon the light was high and the air hot, and we returned back to camp for a quick lunch and a 2:15 return to the park.

PM. We entered the western gate this afternoon, in contrast to the bit more crowded Central Gate where we boarded our elephants this morning. The rhino shooting from the jeeps was outstanding, and we had several opportunities for close-ups as rhinos fed in the open and close to the road. A small herd of wild Indian Elephants visited the lake shore, giving us some OK family shots at some distance in the soft afternoon light. We had a good view of an Asian Barred Owlet and, close by, a poor view of a Brown Fish Owl.

At a viewing platform overlooking Duva Lake a large group of perhaps twenty Smooth-coated Otters (Lutrogale perspicillata) swam about, catching three large fish within a minute of each other. Some charged in to attempt to share but the successful ones seemed to always keep their prize. Occasionally the otters would start calling, sounding remarkably like the Giant Otters of the Pantanal. Unfortunately they never swam close for anything other than tiny white-chinned heads sticking above the river’s surface.

We game-drove until shortly after 6 with the sun dipping a dull red behind the distant western mountains. A bull Asiatic water buffalo floated in the now dingy orange-colored water, its broad, sweeping horns and the boss of its head just visible above the surface. In the starkness of the light the sharp black silhouette of the buffalo accented the shape of the horns, flat, scythe-shaped, and so unlike either its relative the African buffalo or the tiny curly-shaped horns of its domestic relative. As we headed back to camp one Indian Elephant was moving up the highway towards us, carrying a load of banana leaves that extended far out on either side, carrying its dinner home.

Feb. 26. Kaziranga.

Rhesus Macaque Monkeys drinking the nectar from flowers; the lower canine of a One-Horned Rhino is visible -- these teeth are used in fights with other rhinos;

a wild Asiatic Water Buffalo wallowing in the mud.